Introduction

- The Scale of Destruction

- Decisions and Laws Issued by the Assad Regime

- The Challenges of Reconstruction

- The High Cost

- International Sanctions

- Compensation

- Property Rights and Associated Problems

- Regulatory Plans

Recommendations and Results

Introduction

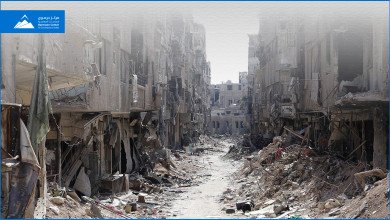

During the Syrian revolution, cities and rural areas across the country suffered the ruination of infrastructure, essential services, and homes. Millions of Syrians were displaced and large sectors of the economy were destroyed. Following the fall of the Assad regime, which played a central role in this devastation, the challenge of physical reconstruction is still becoming clear. This process will involve rebuilding entire cities and neighborhoods destroyed during the war, fostering economic development in these areas, facilitating the return of displaced persons and refugees, and advancing transitional justice hand in hand at multiple levels.

However, any successful attempts at reconstruction will rely on key factors, including adequate funding, engineering and planning expertise, a stable political environment that supports sustainable development, and a secure nation that encourages investment. Decisive action also faces significant obstacles, including the contestation of property rights, the sheer cost of reconstruction, compensation, and the need to re-plan the infrastructure of destroyed areas.

This paper aims to highlight the extent of the destruction caused by the war in Syria. It will focus on the laws issued by the Assad regime regarding property rights and regulations, which have led to the deprivation of many citizens’ rights and property. It also examines the challenges involved in physically reconstructing areas partially or completely destroyed – and offers a set of recommendations to address these issues.

- The Scale of Destruction in Syria

The war in Syrian cities left precious few regions untouched. The neighborhoods of Homs, areas surrounding the capital Damascus, the eastern neighborhoods of Aleppo, and several regions in Deir ez-Zor, Raqqa, and Daraa were all decimated. In these areas, many neighborhoods were either partially or completely destroyed, and the infrastructure was severely damaged. Even in regions that did not directly experience the impact of live conflict, the infrastructure has deteriorated due to neglect. In 2019, the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) published a report that highlighted the extent of the damage in several Syrian cities, including:[1]

In 2022, the World Bank reported that approximately 210,000 housing units had been destroyed in Syria[2]. This number increased yet further following the earthquake that struck Turkey and Syria on February 6, 2023, which affected several Syrian governorates, including Aleppo, Idlib, Hama, Latakia, Homs, and Tartous. The report by the World Bank estimated that the earthquake destroyed about 13.1% of the total buildings in Idlib Governorate and 4.1% in Aleppo Governorate.[3] Other sources estimated that, at that time, approximately 12,795 buildings across Syria were damaged, with 2,691 completely destroyed.[4]

While these reports are valuable for counting the destroyed neighborhoods and buildings, they were based on limited data prior to the fall of the regime. Today, however, Syria is more accessible for comprehensive surveys that can include all areas, giving a more realistic and accurate assessment that can fill the gaps of previous reports. As a result, it is now possible to gather more precise data on the infrastructure destroyed over the past 14 years. The current transitional government should collaborate with international organizations who can help to conduct surveys across the sites affected by destruction in Syria.

- Decisions and Laws Issued by the Assad Regime

After 2011, the Assad regime issued several edicts and decrees disguised as the redevelopment of residential areas. However, their true purpose was to legitimise the seizure of property belonging to opponents or their supporters, particularly in areas where demonstrations broke out and later evolved into armed conflict. In 2012, the regime issued Decree No. 66, which served as a pretext for seizing informal housing areas around Damascus.[5] The regime used this decree to displace much of the population, either following mass massacres and sieges—such as in Daraya, Yarmouk Camp, and al-Hajar al-Aswad—or after expelling residents from areas where protests did not escalate into armed conflict, such as the Basateen al-Razi neighborhoods.

The regime’s goal was to alter the demographic landscape of these areas to prevent future threats. It began constructing towers as part of the Marota City Project. The regime issued regulatory plans for these areas and distributed title deeds, even though many, especially from the opposition, were unable to prove ownership of the properties. The Damascus Governorate also seized 50 plots of land in these areas and sold them to the Sham Holding Company,[6] which promised to provide alternative housing for the displaced residents.

Having studied the laws and decrees used to expropriate property and land in Syria, we highlight several key measures:

- Decree No. 40 of 2012 stipulated the removal of illegal buildings,[7] enabling the demolition of many informal housing areas whose residents had been displaced by the war. This included areas surrounding Daraya, Yarmouk Camp, and al-Hajar al-Aswad, where residents were unable to prove that their properties existed before the decree was issued.

- Decree No. 63 of 2012 authorized the judicial police to seize the properties of individuals accused of terrorism as a precautionary measure.[8]

- Law No. 23 of 2015 granted government bodies the right to deduct a percentage from properties in conflict zones. The deduction could not exceed 40% for properties in rural areas outside regional centers, and 50% for properties within cities. If the deduction exceeded these limits, property owners could only seek compensation for the additional area deducted.[9]

- Law No. 33 of 2017 allowed for the reconstitution of damaged real estate documents.[10] This law was particularly dangerous for enabling the creation of new real estate documents through committees directly affiliated with the Assad regime.

- Law No. 35 of 2017 permitted the precautionary seizure of both movable and immovable assets from individuals who failed to pay the military service allowance.[11]

- Law No. 3 of 2018 granted governors the right to designate certain areas as “building-free” zones, allowing them to be redeveloped.

- Law No. 10 of 2018 enabled the creation of new regulatory areas within broader development plans.[12] This law was seen as an effort to seize the properties of displaced Syrians and preemptively control the distribution and organization of land during future reconstruction, with the goal of altering the social and demographic landscape.

- On November 30, 2023, the People’s Assembly passed a law granting executive authorities the right to manage and invest movable and immovable assets confiscated by final court rulings.[13]

Figure 1: Key Decrees and Laws Issued by the Assad Regime to Seize Property and Real Estate

- The Challenges of Reconstruction

- The High Cost

Vast areas of Syria have been completely destroyed, and rebuilding them requires substantial financial resources. In 2018, the United Nations estimated war-related losses in Syria at approximately $400 billion.[14] These estimates have most likely increased, though the extent varies across reports depending on their areas of focus. There is a clear distinction between the cost of rebuilding destroyed areas and broader war-related losses at developmental and economic levels. In 2019, ESCWA estimated that the material destruction inflicted on Syria over eight years of war amounted to approximately $117.7 billion, while losses in gross domestic product were valued at around $324.5 billion. This brought the total estimated cost of the conflict that year to about $442.2 billion.[15]

The Syrian state cannot shoulder these costs alone, as they far exceed its financial capacity and would take decades to cover. Many hopes are pinned on financial support from Gulf and Western nations – whether through funding infrastructure reconstruction or direct financial aid to the state treasury for sustaining government institutions. The new authorities are also reliant on Turkish support, particularly in the form of consulting services or the involvement of experienced infrastructure development firms to assist in urban planning and reconstruction. Some Turkish companies possess relevant expertise, given the country’s recent urban development and the experience of rebuilding areas affected by the earthquake that struck Turkey and Syria in early 2023.

Figure 2: Total Cost of the Conflict in Syria Until 2019 (ESCWA)[16]

Estimated Cost of the Syrian Conflict (in Billion USD)

Addressing the high cost of reconstruction requires comprehensive and accurate data on the extent of the destruction, as well as the ability to attract international and regional funding, organize donor conferences, and secure investments. Achieving this depends on security and political stability, in the form of a constitutional and consensus-based government capable of engaging with the international community. This government must establish a reconstruction fund, participate in donor conferences, and enact policies that encourage investment—both from foreign sources and from Syrian investors and businesses.

Such stability would also enable the government to conduct a thorough assessment of destroyed areas, with support from international organizations experienced in needs assessment and advanced surveying techniques, such as satellite imaging and drone technology. Beyond the challenge of reconstruction costs, there is an urgent need for immediate interventions, including support for the food, water, and energy sectors and the repair of water and electricity networks in partially damaged areas.

Figure 3: Addressing the Challenges of the Reconstruction Process

The experiences of neighboring countries, such as Lebanon and Iraq, offer valuable lessons for Syria’s reconstruction process, highlighting both successes and challenges. In Iraq, several factors weakened the country’s recovery, including the prioritization of foreign companies, which secured most of the contracts over local companies. Additionally, successive governments focused on security spending rather than development, leading to social and economic marginalization, preventing most Iraqis from directly benefiting from reconstruction efforts.

Lebanon also faced major obstacles in its post-civil war reconstruction. The Lebanese government increasingly relied on loans, which contributed to a crippling economic crisis. Moreover, private companies owned by Lebanese politicians dominated many reconstruction projects, leading to a concentration of economic benefits among the elite, while the broader population saw limited gains.[17]

Figure 4: Reasons for the Weakness of the Reconstruction Process

in Neighboring Countries (Iraq, Lebanon)

- International Sanctions

In discussing the crippling costs of reconstruction, it is crucial to address an exceptionally important issue; namely the Western and American sanctions imposed on Syria, particularly the Caesar Act.[18] These sanctions serve as a major obstacle to the flow of investments and capital into Syria. Until they are lifted, Syria will remain unstable, and dealing with the Central Bank of Syria will remain impossible, leaving the reconstruction process stalled and preventing donor conferences from taking place.

Lifting these sanctions will require political efforts and regional consensus, to convince the West that they must be removed. This also calls for an American commitment to develop and stabilise the region. The formation of Syrian pressure groups in the United States could play a role in this process, alongside a new government in Syria that handles key issues with caution – including relations with Russia and regional security concerns, particularly regarding Israeli security. Additionally, it is essential that the new government be representative of all Syrians.

- Compensation

The issue of compensation is critical to the transitional justice programmes Syria must adopt in rebuilding the state and restoring trust between the government and society. The former Syrian regime created a fundamental void between the state and its citizens, by destroying entire areas in retaliation against those who supported protests. Clearly, compensating individuals whose homes were destroyed by the former regime in the name of the state is not only essential for rebuilding Syria, but it is also a right recognized by international law.[19] Compensation can be divided into two main categories:

- Direct compensation: This involves providing financial compensation to property owners whose homes were destroyed, and offering an emergency solution that allows them to find shelter until reconstruction begins. However, a potential issue arises in determining who qualifies for compensation—should it be the homeowner or the tenant? Should compensation be the same for those who own multiple properties as for those who own only one? Does the compensation only cover homes, or does it extend to other destroyed properties, such as shops and recreational villas that may not be widely owned? Addressing these questions requires balancing a sense of just compensation—ensuring all affected individuals are included—against spiralling costs, which could reach billions of dollars and cannot be paid all at once. Therefore, it might be more practical to provide minimum compensation that includes all affected parties. This compensation would focus directly on damaged property and offer emergency assistance with temporary housing.

- Indirect compensation: This involves providing opportunities for small and medium-sized local businesses. The government should not rely solely on large contracting companies with the potential to dominate the entire reconstruction market, deepening the divide between society and state. It is essential to involve local small and medium-sized enterprises to stimulate the local economy, create jobs, and increase public confidence in the state and its decisions. The post-war reconstruction process must focus on sustainable development. Its goals should address the economic factors that contributed to the conflict in Syria, support and expand the middle class, and enhance its development in terms of education, economy, and services. This approach will benefit both the state and society, and form an integral part of indirect compensation.

The challenge of providing compensation during the reconstruction process is a significant one. On the one hand, it is crucial for the new state to rebuild trust with its citizens. On the other hand, compensating those who are entitled requires vast sums of money, which the state cannot afford on its own, as its own coffers have been so comprehensively depleted by the Assad regime’s spending on war and corruption.

Figure 5: The Role of Compensation in State Building

- Property Rights and Associated Problems

Real estate ownership in Syria is categorized into five types, the most important of which is the green title deed, the strongest official document proving ownership. Another type is ownership by court ruling, where a Syrian court confirms an individual’s right to a property based on decisions issued by the competent court. Another form is irrevocable power of attorney, where the buyer receives authorisation from the owner to transfer property ownership to themselves or another party.

There is also ownership through a final sale contract, an agreement between two or more parties in which the owner agrees to transfer property ownership to the buyer, who in turn agrees to pay a specific sum. Lastly, there is ownership through the purchase of a share of a property in common, typically when the property is jointly owned by several individuals with undivided shares – such as in the case of transferring ownership to heirs after the owner’s death, without specifying each heir’s share.[20]

Figure 6: Types of Property Ownership in Syria

After determining eligibility for compensation, the next challenge lies in proving ownership – a problem faced by many Syrians, particularly in informal housing areas. A significant portion of real estate records have also been damaged or forged in recent years. Addressing the legal issues surrounding property deeds, especially in areas slated for reconstruction, requires understanding the legal status and complications of real estate in Syria before the war, and considering the complications that arose after the war began. Many Syrians lacked strong deeds proving ownership, relying instead on sales contracts, notarised documents, or utility bills.

Some property ownerships were communal, without specific descriptions of the residences or their locations. A 2007 report by the Central Bureau of Statistics indicated that informal housing in cities accounted for about 40%, with roughly 60% of those properties lacking regular title deeds.[21] After the outbreak of the Syrian revolution, the Assad regime enacted several laws to seize the properties of those opposing the regime, such as Decree 63 of 2012, which allowed judicial police to freeze assets without a court order.[22]

Many properties were sold under duress to influential figures affiliated with the regime or to non-Syrian individuals linked to Iranian, Lebanese, and Iraqi militias.[23] Numerous property owners have also disappeared or gone missing in recent years, leaving their families unable to conduct inheritance procedures until their fates are determined. The need to resolve these legal issues is particularly urgent with the return of displaced persons and refugees. Those whose homes remain intact can return and address their legal problems later. However, those whose homes were destroyed face the dual challenge of proving ownership while potentially waiting for decisions from the relevant authorities regarding the reconstruction and organisation of these areas. This is especially true for completely destroyed areas, such as those in Homs, Deir ez-Zor, and neighborhoods surrounding Damascus, where both residential buildings and infrastructure need rebuilding.

Figure 7: Addressing Property Rights Issues

The new government must revise or amend the laws issued by the former regime and establish official committees to adjudicate foreign ownership and identify usurped properties for return to their rightful owners. To address these legal challenges, the government should also empower community leaders and civil councils to help resolve property issues locally before they reach the courts. Additionally, committees comprising local leaders should be formed to verify properties that existed in neighborhoods before they were destroyed during the war. These committees can use old satellite images to confirm the properties’ existence and specifications, comparing these findings with the results they gather.

- Regulatory Plans

Before 2011, Syria’s population was growing without any serious plans to expand regulatory frameworks in the cities to match. As a result, many people sought homes in informal housing areas, drawn by their proximity to city centres, low cost, and the availability of basic services – albeit at a minimal level. These areas were considered violations of urban planning norms. In 1982, the Central Committee of the Baath Party decided to provide basic services to these informal areas,[24] rather than enacting laws to expand regulatory frameworks that would meet the city’s social, economic, and environmental needs. After the onset of the Syrian revolution and the subsequent destruction of cities and neighborhoods that had supported the protests, the Assad regime sought to reshape some of these areas by drawing up new regulatory plans.

To facilitate this, the regime enacted laws allowing for the expropriation of properties belonging to its opponents. Efforts to slowly rebuild began in some suburbs of Damascus, such as the Marota City and Basilia City projects.[25] In Aleppo, the regime attempted to promote the ‘Tomorrowland’ project on the Northern Ring Road.[26] However, these initiatives were hindered by economic sanctions and the high costs associated with rebuilding these neighborhoods. When examining these plans, it becomes clear that they were part of a broader process to legalise the violation of Syrians’ property rights. This was compounded by illegal actions taken by influential regime-affiliated figures, including forging title deeds and purchasing properties under duress.

Figure 8: The Strategy of Regulatory Plans in the Reconstruction Process

When preparing new regulatory plans, authorities must take into account the Assad regime’s violations committed against property owners in areas slated for reconstruction. Implementation should not begin until property rights are restored and related legal issues are fully resolved. When addressing real estate legal challenges, it is also essential to involve the local community in planning and organizing these areas. This can be achieved through direct meetings and workshops with affected communities, or by engaging relevant unions and civil society organizations involved in physical, social, and economic reconstruction.

Each area has distinct cultural, social, and economic characteristics, including local customs, professions, and geographical factors that must be considered on a granular level. Planning must be tailored to the specific needs of each city or region. Successful reconstruction requires the majority of displaced residents to return home, especially Syrian refugees living in exile. It must also be accompanied by transitional justice initiatives – as seen in other post-conflict contexts such as Rwanda – where reconstruction efforts were integrated with transitional justice measures.[27]

Development and reconstruction should proceed alongside efforts to commemorate victims of the Assad regime’s violations and mass massacres. This could be reflected in new regulatory plans through memorials or national museums documenting the personal narratives of those affected during the years of the revolution.

In developing new regulatory plans, it is essential to acknowledge that those introduced by the Assad regime during the revolution were designed to alter the social fabric of areas where protests began in 2011. These plans ignored the root causes of the uprising – namely underdevelopment, high unemployment, low per capita income, and inadequate health and education services. The regime operated on the assumption that most Syrian refugees would not return, allowing it to consolidate control over the remaining population while dispossessing its opponents of their properties. This strategy not only deprived exiled Syrians of their rights but also suppressed dissent among those who remained. Following the regime’s fall and the return of displaced Syrians, the new government must ensure that reconstruction aligns with economic and educational development.

Regulatory plans should reflect both a national need for modernization and the unique needs of communities and families. Rebuilt areas should include shelters, gardens, open spaces, and safe environments for children. Additionally, economic realities—whether in agriculture, industry, or trade—must be carefully considered for each region. This can only be achieved through direct engagement with local residents and collaboration with civil society organizations working on the ground.

The development of new urban infrastructure may also be challenged by the expansion of informal housing, which has resurfaced in several areas. Over the past two months, this trend has been particularly evident in suburbs, including those surrounding Damascus. Some individuals construct homes for personal use, while others build villas and resorts in agricultural zones for commercial or recreational purposes. These developments are taking place illegally and could obstruct the reconstruction process, or delay fresh regulation that balances agricultural and residential needs in rural areas. The government must urgently address these violations now – to prevent them from escalating in the future.

Recommendations and Results

- Prioritize emergency provision to the food, water, and energy sectors, while repairing water and electricity networks in partially destroyed areas.

- Attract international and regional funding, along with investment and capital, which requires security and political stability through constitutional and consensus-based governance.

- Coordinate government efforts with international organizations to conduct comprehensive and precise surveys of destroyed areas, leveraging advanced tools and expertise.

- Rescind the laws and decrees issued by the Assad regime during the revolution, which were designed to confiscate the property of political opponents and their support base.

- Address ownership ambiguities, particularly in informal housing areas, by involving local communities and civil society organizations in resolving these issues before they escalate to the courts.

- Establish specialized committees to assess foreign ownership and identify seized properties.

- Engage communities in the planning process to ensure that new development frameworks reflect their aspirations, cultural identities, and economic needs through civil councils and unions.

- Create a reconstruction fund and organize international donor conferences to secure financial contributions.

- Encourage small and medium-sized businesses to participate in the reconstruction process of their local areas, fostering economic growth and strengthening public trust in the state and its policies.

- Integrate economic and educational development initiatives into the re-planning of destroyed areas to support long-term recovery.

References

Central Bureau of Statistics. (2007) Informal settlement areas in Syria. Available at: http://cbssyr.sy/studies/st24.pdf.

Humanitarian Library. (2020) Syrian cities damage atlas. Available at: https://2u.pw/OOtBQfbs.

Adi, M. (2023) ‘The right to slums: In defense of “violations” neighborhoods in Syria’, Al-Jumhuriyya. Available at: https://2u.pw/lvhGtpYs.

ReliefWeb. (n.d.) The Pinheiro Principles: United Nations principles on housing and property restitution for refugees and displaced persons. Available at: https://2u.pw/MFTqIY8h.

Abboud, S. (2014) ‘Comparative perspectives on the challenges of reconstruction in Syria’, Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center. Available at: https://zt.ms/39U.

Syrian Center for Policy Research. (2023) Earthquake effects in Syria: The missing development approach in the shadow of conflict. Available at: https://2u.pw/53yPDA1y.

World Bank Group. (2023) Syria earthquake 2023 – Rapid damage and needs assessment. Available at: https://2u.pw/osMRde5R.

World Bank Group. (2023) Global rapid post-disaster damage estimation (GRADE) report: MW 7.8 Türkiye-Syria earthquake – Assessment of the impact on Syria. Available at: https://2u.pw/DcW1W2ms.

World Bank Group. (n.d.) Syria-joint damage assessment of selected cities. Available at: https://2u.pw/yYwPW3ST.

[1] Syrian Cities Damage Atlas, Humanitarian Library, Oct. 2020: https://2u.pw/OOtBQfbs

[2] Syria – Joint Damage Assessment of Selected Cities, 28 February 2023: https://2u.pw/yYwPW3ST

[3] MW 7.8 Türkiye-Syria Earthquake – Assessment of the Impact on Syria: Results as of February 20, 2023, Global Rapid Post-Disaster Damage Estimation (GRADE) Report: 3 March 2023: https://2u.pw/DcW1W2ms

[4] Earthquake Effects in Syria: The Missing Development Approach in the Shadow of Conflict, Syrian Center for Policy Research, September 3, 2023, accessed February 12, 2025: https://2u.pw/53yPDA1y

[5] “Legislative Decree No. 40 of 2012,” Syrian People’s Assembly, May 20, 2012, accessed February 12, 2025: https://2u.pw/ANwqmHql

[6] “Marota City: What is Damascus Cham Holding Company?” Al-Modon, April 19, 2019, accessed February 12, 2025: https://2u.pw/zL3KktEz

[7] Legislative Decree No. 40 of 2012, Syrian People’s Assembly, May 20, 2012, accessed February 12, 2025: https://2u.pw/ANwqmHql

[8] Legislative Decree No. 63 of 2012, Syrian People’s Assembly, September 16, 2012, accessed February 12, 2025: https://2u.pw/7YJQXtIb

[9] Law No. 23 of 2015 on the Implementation of Urban Planning and Development, Syrian Council of Ministers website, December 18, 2015: Accessed February 12, 2025: https://2u.pw/3bpMSr

[10] President Bashar al-Assad Issues Law No. 33 Regulating the Restoration of Lost or Damaged Real Estate Documents, Ministry of Local Administration and Environment, October 29, 2017, accessed February 12, 2025: https://2u.pw/YUzJ0WN7

[11] Law No. 35 of 2017 Amending the Military Service Law Issued by Legislative Decree No. 30 of 2007, Syrian Council of Ministers, November 15, 2017, accessed February 12, 2025: https://2u.pw/w3LRTU3Z

[12] Law No. 10 of 2018: Authorization for Establishing Regulatory Areas within the Regulatory Plan, e-Government Portal, November 28, 2018, accessed February 12, 2025: https://2u.pw/vBFeLTCj

[13] The People’s Assembly Approves Draft Law on Managing and Investing Movable and Immovable Assets, Syrian People’s Assembly, November 30, 2023, accessed February 12, 2025: https://2u.pw/eGSKnN2

[14] New UN figures on the Cost of Rebuilding Syria, Enab Baladi, August 9, 2018, accessed February 12, 2025: https://2u.pw/sE2xdt8A

[15] Losses Exceeding $442 Billion and Millions in Need of Humanitarian Assistance: The Catastrophic Repercussions of 8 Years of War in Syria, ESCWA, 23 Sep 2020: https://2u.pw/CckgCL27

[16] Ibid.

[17] Comparative Perspectives on the Challenges of Reconstruction in Syria, Samer Abboud, Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center, December 30, 2014, accessed February 14, 2025: https://zt.ms/39U

[18] Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act, The U.S. Department of State: https://2u.pw/ZgI1yPQX

[19] The Pinheiro Principles: United Nations Principles on Housing and Property Restitution for Refugees and Displaced Persons, ReliefWeb, 1 Dec 2005: https://2u.pw/MFTqIY8h

[20] Types of Real Estate Title Documents, Housing, Land and Property Rights, June 30, 2021, accessed February 13, 2025: https://2u.pw/FlR7skmp

[21] Informal Settlement Areas in Syria, Central Bureau of Statistics, 2007, accessed February 12, 2025: http://cbssyr.sy/studies/st24.pdf

[22] Legislative Decree No. 63 of 2012, Syrian People’s Council, September 16, 2012, accessed February 12, 2025: https://2u.pw/7YJQXtIb

[23] Foreigners’ Real Estate in Syria: A Complex Issue Facing the New Administration, Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, January 14, 2025, accessed February 12, 2025: https://2u.pw/zem5oPni

[24] The Right to Slums: In Defense of ‘Violations’ Neighborhoods in Syria, Mazen Adi, Al-Jumhuriyya, November 20, 2023, accessed February 12, 2025: https://2u.pw/lvhGtpYs

[25] Four Years After ‘Basilia City’: Consolidating Displacement in the Name of Development, Enab Baladi, March 26, 2022, accessed February 12, 2025: https://2u.pw/7s5kEPXb.

[26] The Assad Regime Promotes an Emirati Tourism Project in Aleppo, Al-Muharrar, May 29, 2023, accessed February 12, 2025: https://2u.pw/oETNrq1L

[27] “The Experience of Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Rwanda: Lessons Learned and Prevention,” Policy Center for the New South, April 18, 2023, accessed February 12, 2025: https://2u.pw/fe7nKF4U