Abstract

This piece examines the transformative aftermath of the Assad regime’s collapse on December 8, 2024, with Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) leading the Deterrence of Aggression operations room to gain control over significant Syrian territories. Ahmad al-Sharaa’s emergence as the interim ruler marks a pivotal transition in Syrian governance amidst a backdrop of over six decades of Baathist oppression. The paper delves into the complexities of Syria’s contemporary landscape, characterized by deep-rooted corruption, societal fragmentation, and extensive material destruction. Immediate priorities identified include stabilizing the nation, ensuring security, and curtailing rampant factionalism and weaponization. In the long term, the focus transitions toward comprehensive reconstruction efforts and the establishment of a governance framework that aligns with the aspirations for freedom and dignity expressed by the Syrian populace since 2011. This analysis underscores the dual imperative of addressing urgent security needs while fostering a resilient, democratic future for Syria.

Introduction

A secure transition from the old Syria to a new political framework necessitates a multifaceted set of conditions, the most critical of which is the presence of inclusive leadership dedicated to engaging all stakeholders in the process of establishing a stable political transition. This commitment must be articulated through a clear and actionable transitional program, with its implementation overseen by a representative body that reflects the diverse forces and components of Syrian society, all united in their dedication to the success of this transitional phase.

Despite the significance of this transitional period, Ahmad al-Sharaa has yet to deliver a comprehensive official address to the Syrian populace or announce a specific program outlining the transitional phase. Furthermore, no official document has been released to delineate a roadmap detailing the stages of transition, their respective priorities, and the executive actions required for each phase. Nevertheless, al-Sharaa and the caretaker government he has established are making pivotal decisions aimed at stabilizing the current situation, some of which extend beyond the powers typically allotted to an interim authority in preparation for the establishment of a full transitional government. Al-Sharaa’s authority is derived from what is termed “revolutionary legitimacy,” which commences with the assumption of power and culminates in a shift toward constitutional legitimacy.

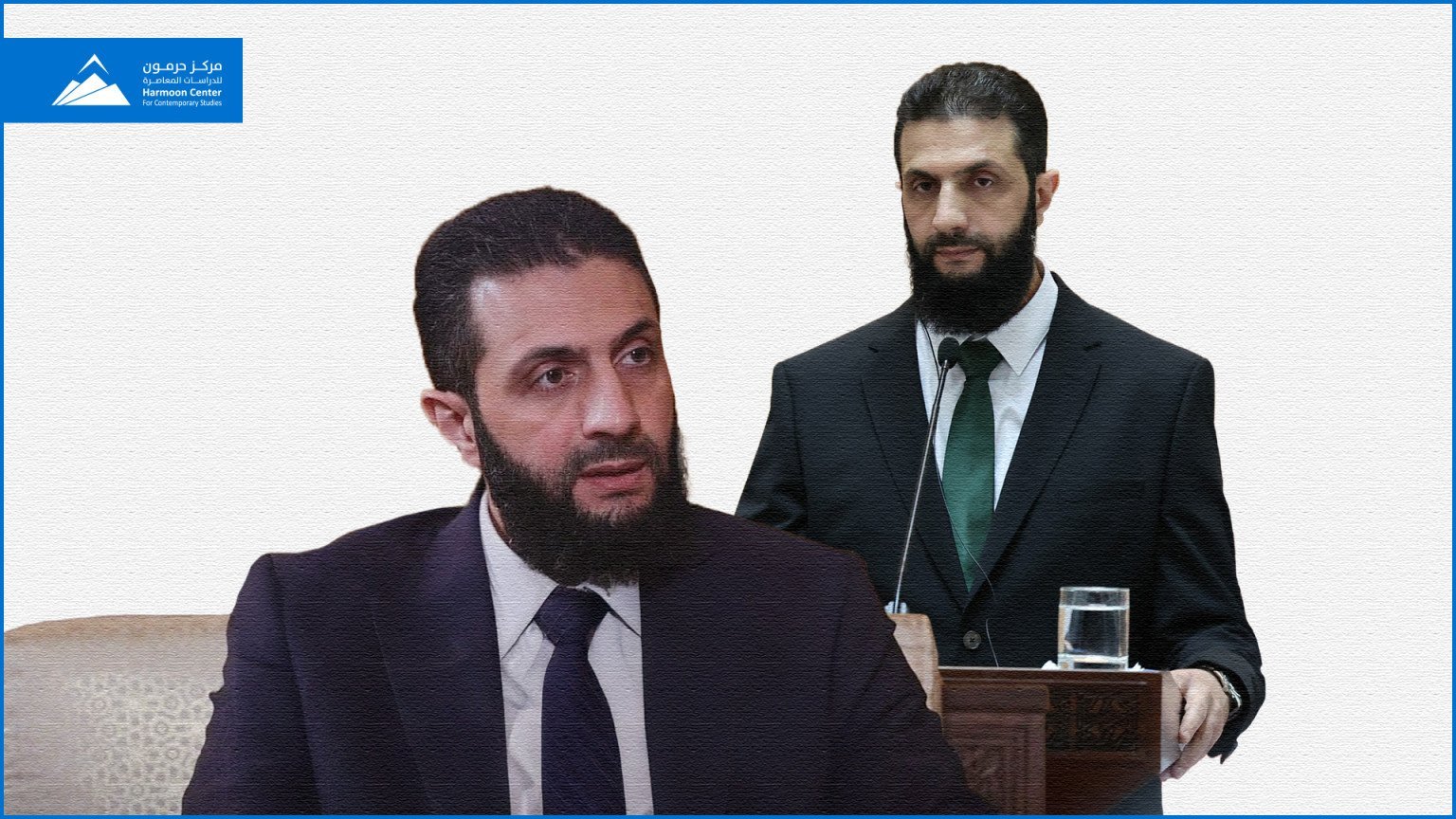

In the absence of a formally articulated vision, this paper analyzes statements made by Ahmad al-Sharaa during media interviews with the BBC on December 19, 2024, Al-Arabiya on December 29, 2024, and YouTuber Joe Hattab, which aired on January 6, 2025. While these statements provide limited insight, they nonetheless contribute valuable perspectives on his aspirations and strategic plans for Syria in the post-Assad era. The key issues he addressed include:

The Nature of the de Facto Authority and the Transitional Phase

Al-Sharaa outlined a vision for rebuilding the Syrian state in light of the transformations the country is undergoing. His approach emphasizes taking control of and preserving state institutions. He stressed the priority of assuming power without damaging these institutions, ensuring the continuation of essential services for the people. This strategy aims to prevent an institutional vacuum that could lead to chaos and complicate reconstruction efforts in the future.

Al-Sharaa’s media statements revealed his vision for establishing a transitional authority, one that prioritizes institutional harmony and efficiency, in contrast to the failed quota system seen in neighboring countries. He emphasized the importance of integrating and communicating across institutions, warning against the danger of fragmenting them into isolated entities or using them as tools for factional interests. He argued that the transitional phase requires selecting competent and experienced cadres to ensure stability and lay the foundations for effective governance. Al-Sharaa justified the appointments he made, which were predominantly of a single hue, by explaining that they were necessary for this stage. In his Interview with Al-Arabiya, he stated: “In transitional phases, you need a harmonious work team. At this stage, we do not want to distribute institutions and ministries as gifts to ethnicities, sects, and parties.”

This proposal, which excludes political pluralism during the transitional phase, has sparked criticism and concerns about how political balance and representation of all components will be ensured in the initial phase. However, in his Interview with Al-Arabiya, al-Sharaa suggested a gradual transition to an interim government formed through the National Congress. This would provide a broader platform for partnership between various political and social groups, once institutional stability is achieved and efficiency is ensured:

I seek competencies, so in the first stage, we rely on those who have successfully managed certain aspects of work to ensure harmony. Then, when we transition to a long-term interim government, there will be participation from various political and social spectrums. (Interview with Al-Arabiya)

The Interim Constitutional Declaration and the Permanent Constitution

The constitution serves as the foundational document that shapes the political, administrative, economic, social, and cultural systems of every modern state. During the transitional phase, a temporary constitutional declaration is typically issued, developed through consensus among representatives of Syrian society in a national conference held for this purpose. Although al-Sharaa did not mention the idea of a temporary constitutional declaration in his discussions, he emphasized the need for clear standards to govern the country during the transitional phase, notably through the redrafting or amendment of the constitution.

Al-Sharaa appears to recognize that this process will take years. Additionally, he emphasizes the importance of addressing the demographic changes resulting from displacement and asylum, particularly focusing on the new generation that has grown up under these shifting circumstances.. This will require extensive statistical efforts over several years to ensure the inclusion of all:

The new Syrian situation will go through several stages. The first stage involves taking control of power, ensuring that state institutions do not collapse. The second stage will be a transitional phase, which must meet certain criteria. For anyone wishing to lead Syria in this scenario, the first step is to either rewrite the constitution or dissolve the previous one. However, drafting a new constitution or making constitutional amendments is a lengthy process, possibly taking two or three years—only God knows. (Al-Arabiya Interview)

Al-Sharaa emphasized that drafting the constitution would be a purely legal matter, which suggests a more technical than political approach. However, he noted that the drafting of the constitution is primarily a political decision, as it defines the general direction of the constitution and the nature of government. Constitutional lawyers, in turn, follow these political determinants when drafting the text of the constitution:

I mentioned that the constitution will go through several stages. First, it will be drafted, but it is too early to discuss any specific steps. Syria is currently facing numerous challenges, including a destroyed infrastructure, a collapsed agricultural sector, and a devastated industrial sector. Additionally, there are regional challenges that require urgent solutions. I believe there are many details I cannot address at this moment, as they are purely legal matters. (BBC Interview)

The emphasis on technical aspects over political considerations in drafting the constitution raises concerns about the level of public participation in the constitutional process. Al-Sharaa’s vision for the new constitution remains unclear, as it lacks details on mechanisms for popular involvement or democratic guarantees. This ambiguity raises questions about how open the new political system will be to pluralism and public participation.

Al-Sharaa advocates for an institutionalized government system in Syria, grounded in the rule of law, rather than an arbitrary, individual authority. He criticizes the Assad regime’s decades-long rule, marked by repression, violence, and displacement. While he affirms the people’s right to freely choose their leaders, he does not outline clear mechanisms to ensure the integrity of this process. Al-Sharaa also defends the concept of Islamic rule, attributing people’s fear of it to poor implementation or misunderstanding. However, he does not clarify how it aligns with the principles of democracy, human rights, and citizenship values: “People who fear Islamic rule have either witnessed its misapplication or do not fully understand it” (CNN Interview).

Al-Sharaa emphasizes that the form of the state and its constitution should be determined by specialized committees selected by the people, rather than through individual decisions. He denies any intention to alter the country’s demographic structure and underscores the importance of preserving its diversity. However, his vision remains vague regarding the most suitable political system for Syria and the guarantees for ensuring the participation of all parties in shaping the country’s future.

National Dialogue Conference

A comprehensive national conference serves as the bridge for transitioning from “revolutionary legitimacy” to constitutional legitimacy. This transition provides the de facto authority with the necessary legitimacy to validate its actions and grants it broader, more comprehensive powers than those held by the interim authority prior to the start of the transitional phase.

Al-Sharaa outlined a pivotal vision for the role of the Syrian National Congress in shaping the country’s future. He emphasized that the Congress is a crucial step toward achieving national consensus and establishing a comprehensive political system that reflects the aspirations of all Syrians. According to him, the Congress aims to engage all political, social, and sectarian components in making key decisions, prioritizing inclusiveness and independence while avoiding any political or military interference to ensure its success and credibility.

According to al-Sharaa, the conference could address key issues such as drafting a new constitution, achieving transitional justice, and establishing a form of government that ensures fair representation for all Syrians. He highlights the importance of focusing on national reconciliation and alleviating social tensions. Al-Sharaa believes the conference’s outcomes should be binding and genuinely reflect the will of the people:

The conference will be inclusive and bring together a wide range of Syrian society’s components. Traditionally, after revolutions, major decisions are often made by the authority that has seized power, typically through military force. I want to steer Syria away from such practices. Heavy decisions, such as dissolving the constitution or parliament, should not rest with a single individual. Instead, I aim to provide all of Syria with the opportunity to participate in these crucial matters. During the conference, we will present the Syrian issue in detail and share all relevant data, including what we have discussed thus far. Ultimately, the conference participants will vote on the critical and sensitive issues that will shape the transitional phase. (Al-Arabiya Interview)

This proposal faces several challenges that require urgent and detailed attention. There are no clear mechanisms for selecting conference participants, raising concerns about achieving comprehensive and fair representation for all parties. This is particularly worrisome given that the interim authority has so far excluded broader participation, with a one-dimensional approach prevailing. Additionally, the lack of a specific timetable and clearly defined outcomes adds to the uncertainty. The conference also requires practical measures to ensure its success as a cornerstone for building a sustainable political future for Syria. There is also a fear that it could devolve into a mere consultative gathering, leaving final decision-making power with al-Sharaa rather than the conference itself.

Syrian Territorial Integrity, Federalism, and Decentralization

Al-Sharaa emphasized that the solution in northeastern Syria must preserve the country’s unity, rejecting any form of division, including federalism. He believes Syrian society is not ready to embrace federalism, as it may be perceived as a step toward secession. This stance reflects opposition to an independent Kurdish entity, yet he acknowledges the need for a political solution that safeguards Kurdish rights without compromising national unity. He affirmed that the Kurds are an integral part of the Syrian people and have faced injustice like other Syrians, necessitating measures to protect their rights and ensure their return to the villages from which they were displaced during the revolution. Regarding the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), al-Sharaa insists that weapons must be centralized under the Syrian Ministry of Defense, with those wishing to join the regular army being accepted based on specific criteria:

Anyone armed in northeastern Syria must have their weapons restricted and kept solely under the control of the Ministry of Defense. Those qualified to join the Ministry of Defense are welcome to do so. Based on these conditions and requirements, we are opening a negotiation path with the SDF, keeping the dialogue open until we find a solution that suits the Syrian situation. (Al-Arabiya Interview)

This proposal reflects a desire to integrate the armed elements as individuals within the new national army, rather than allowing them to remain an independent force. The Kurds emphasize the need for guarantees to protect their interests in any future agreement, which could complicate negotiations with the SDF and present significant challenges. This is particularly relevant given the uncertainty surrounding the US position on its future presence in Syria under Trump administration.

The Religion-State Nexus

Al-Sharaa believes that Syria should remain a multi-sectarian state, arguing that emphasizing this issue only incites division. He stressed that the constitution should be the authority responsible for regulating such matters. He rejected comparisons between Syria and Afghanistan, noting that Syrian society is fundamentally different from Afghanistan’s tribal society, which means that governance in Syria will be more aligned with its unique culture and history: “No one has the right to erase another group. These communities have coexisted in this region for hundreds of years, and no one is entitled to eliminate them” (CNN Interview).

In fact, al-Sharaa avoided any statements that might suggest the neutrality of the state, refer to democracy, or address the role of the new authorities in relation to the Islamic character of the regime. This approach is understandable given the current context. He also refrained from answering specific questions about issues such as the imposition of the veil on women or the freedom to consume alcohol. Despite this, all of the ministers, governors, and army officers he has appointed, along with those placed in government departments, are fighters from HTS who support an Islamic political system. From this, we can conclude that while al-Sharaa, who aspires to the presidency of Syria, acknowledges that a strict Islamic model may not be suitable for the country, the method by which he has seized power is strongly aligned with a religious state orientation. The question remains: how will he navigate this conflict?

Stance on UN Resolution 2254

It is no surprise that Ahmad al-Sharaa will reject Resolution 2254 and any political role for the United Nations in Syria beyond providing humanitarian aid. This is because the resolution stipulates “for Member States to prevent and suppress terrorist acts committed specifically by Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant,” and it explicitly names al-Nusra Front. More importantly, the resolution calls for “the establishment of an inclusive transitional governing body with full executive powers” and specifies that the political transition in Syria must be “under UN auspices, on the basis of the Geneva Communiqué.” It also outlines that the United Nations is to facilitate the political process and oversee the holding of free and fair elections. Al-Sharaa cannot agree to these conditions because they would remove control of the political process from his hands. As a result, al-Sharaa rejected Resolution 2254, stating that it has no place in the new phase:

The resolution was issued in 2015, and now, at the end of 2024, the situation has dramatically changed. The battle has shifted the landscape, and these new developments must be considered when implementing the resolution. This is what we communicated to the UN envoy—that a lot has changed in the past stage, and we have moved beyond the core of the resolution. (Al-Arabiya Interview)

Al-Sharaa emphasized that international laws and resolutions should be flexible and adapt to changing circumstances. He noted that the military actions in Syria have aligned with the core goals of Security Council Resolution 2254, which aims for a comprehensive political transition, the return of refugees, and the release of detainees. He argued that the key provisions of Resolution 2254 have already been achieved: refugee returns are now safe, detainees have been released, and power has been peacefully transferred following Assad’s escape and the assumption of power by the new government. Therefore, he believes there is no need for Resolution 2254 anymore. In contrast, the statements from the Aqaba and Riyadh Conferences reaffirm Resolution 2254 and the transitional governing body, reflecting the views of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, and even Europe.

Public Freedoms and Human Rights

Public freedoms, including those of organization, expression, and belief, along with human rights protected by law and the values of citizenship, form the backbone of the political system in a modern state. These principles will serve as the benchmark for evaluating the political system that will be established in Syria in the coming period.

Ahmad Al-Sharaa clearly criticized the former regime in Syria, highlighting that it had transformed the people into a constant enemy to be feared. He believed the regime’s downfall liberated the people from this fear, as evidenced by their newfound ability to express themselves freely without the threat of repression:

Now, anyone can express their opinion freely, as long as it doesn’t violate the law, damage public property, or disrupt community life. Today, there is a strong societal consensus in Syria that has the potential to create a new way of life—one that the people have not experienced in 50 years. (Al-Arabiya Interview)

Al-Sharaa did not provide a clear formula for guaranteeing public freedoms in organization, expression, and belief, and he never mentioned “human rights” or “citizenship,” which are fundamental pillars of contemporary societies. When asked directly about issues such as the sale of alcohol and the imposition of the veil on women, he avoided giving explicit answers, stating:

Regarding alcohol, there are many issues I cannot address because they are purely legal matters. A legal committee will oversee the constitution, and it includes many experts and reputable legal figures from Syria. They will make decisions on these issues, and the role of any leader is to implement the laws agreed upon by these committees. (BBC Interview).

Al-Sharaa’s insistence on separating his personal decisions from public laws reflects his attempt to avoid controversy regardinghis role in shaping society. However, he does not adequately clarify the extent of state intervention in social issues, which could affect public freedoms in the future. While he has expressed clear positions on many matters, leaving the door open to imposing strict rulings raises concerns and questions about the balance between individual rights and societal traditions..

Stance on the Opposition

Opposition is a cornerstone of any contemporary political system, serving as a safeguard against tyranny by providing individuals and society with a platform for expression and protest, fostering creativity and development. Al-Sharaa has expressed support for the existence of opposition, stating, “There is no one whom all the people of the country agree on, meaning that some objections occurred, and this is a natural right, and it is something enriching” (BBC Interview). Regarding accusations of violence against the opposition in Idlib, he acknowledges the presence of objections but views them as a natural right. However, he stresses that any attacks on public institutions are met with legal action, not excessive force. As for the possibility of demonstrations in Damascus, al-Sharaa affirms that the right to protest is legitimate, but he sets legal conditions to regulate it, distinguishing between peaceful demonstrations and assaults on public property. While this position appears balanced in theory, its effectiveness will depend on the independence of the security and judicial systems in handling protests and, importantly, on the content of laws and the restrictions they place on public freedoms:

The law was applied to those who attacked public institutions. While people have the right to object to specific matters or decisions, if they attack institutions, destroy property, burn buildings, or block roads, they will be held accountable, as these actions harm the public interest. (BBC Interview)

However, in another statement, he emphasized:

The situation in the country cannot tolerate divisions. There were institutions opposing the former regime, but now that regime is gone. I say, let us all unite under the umbrella of the state to build a law, a constitution, and a major strategic plan for the country. We do not need separate institutions when the state is present. (Al-Arabiya Interview)

This contradiction and lack of clarity on public freedoms and opposition activity raise concerns about the new authority’s ability to accommodate political pluralism, especially if opposition parties challenge al-Sharaa’s vision. Will the formation of independent political parties that oppose the new authority be allowed to operate freely, or will they be restricted by narrow, stringent laws designed to limit public freedoms and control society politically, rather than ensuring freedom of expression?

Economic System

The vision of the new authorities, including al-Sharaa’s, appears vague or insufficient, particularly concerning the economic system. There seems to be a lack of qualified cadres who can formulate a thoughtful economic direction tailored to the conditions of a country like Syria, which has endured nearly 14 years of devastating war, preceded by more than five decades of authoritarian rule. Based on statements from al-Sharaa, some ministers in the caretaker government, and various decisions, it appears there is an initial understanding that Syria will transition toward a capitalist market economy. This would involve reducing the state’s economic role, privatizing the public sector, and abandoning subsidy policies, which are viewed as “socialist.”

There is a discernible urgency in the government’s approach to major economic decision-making, often undertaken without adequate deliberation. For instance, the recent issuance of an ambiguous customs tariff exemplifies this tendency. Furthermore, the government has announced plans to privatize all public sector enterprises, encompassing key industries such as electricity generation and distribution, cement production, banking, and others. It is important to note that Syria’s economy was never truly socialist. The policies of the Baathist Assad regime, since Hafez al-Assad seized power in 1970, were not rooted in ideological principles but were driven by calculations aimed at consolidating power and supporting “crony capitalism,” as the Egyptian expression puts it. Furthermore, policies designed to support certain sectors or consider the social aspect, particularly the conditions of those with limited incomes, are not exclusive to socialist economies. These are also common in free market economies, as seen in European countries, which, while adhering to market economy principles, also manage institutions with a social focus. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries provide another example of states with a strong economic role, including a productive and service-based sector. It is clear that the neo-conservative liberal economic model would severely harm Syria, which is recovering from an economically and socially devastating war. The state must therefore play a leading role in managing and directing the development process, with a direct interventionist economic role within defined limits. At the same time, the economy should remain governed by free market principles, with the private sector as the main engine of growth and investment. This should be guided by a strategic vision developed by the state in collaboration with experts and specialists.

Stance on State Institutions

Although Resolution 2254 calls for the preservation of existing state institutions to prevent chaos, the position of the new authorities, including al-Sharaa’s statements, seemed to take a negative stance towards these institutions. For instance, if the army, security forces, and police were to be dissolved, they would effectively be deprived of their salaries, especially given the uncertainty surrounding their future. In contrast, the administration brought in a small security and police apparatus from Idlib, which is insufficient to meet Syria’s needs, and also opened the door to enlistment in the police force. Furthermore, the new treated employees of state institutions as expendable, retaining only those considered essential by the regime.

Restricting the Possession of Weapons to the State

Al-Sharaa has repeatedly expressed his intention to dissolve HTS and all other factions, integrating their members into the national army and transitioning from a factional state to a national state. He outlined a legal and diplomatic approach to resolving the issue of disarming armed factions, emphasizing that the law should be the primary guiding principle. This reflects a desire to achieve state sovereignty in an organized manner, without resorting to direct conflict. He stressed that the solution will involve negotiation and consultation, with the goal of creating a unified state where weapons are held exclusively by the official authorities. This position aligns with international standards for state-building following conflicts:

I believe the law will ultimately decide the outcome. If they insist on the presence of the state, then these weapons will be deemed illegal. Through negotiation, consultations, and dialogue, we will work towards a point where Syria is unified under one authority, with weapons in the hands of the state alone. (BBC Interview)

This proposal faces several significant challenges. The first is that the factions will not lay down their weapons unless they are included in power. The second is that some factions want to integrate into the army as units, which would perpetuate the factional spirit, while state stability requires their integration as individuals. The third challenge is that the total number of factions exceeds the needs of the national army, which is estimated to require about 100,000 personnel. Additionally, the army needs specialized skills that the factions do not possess, meaning there is a surplus that will need job opportunities, which could be provided through reconstruction. The worst alternative, as seen in some countries, is to pay salaries to this surplus while they remain idle. Another issue worth mentioning is the rumor about abolishing compulsory military service in Syria. We believe compulsory military service is a “national need,” as it serves to integrate people from distant regions and familiarize them with one another’s cultures. Moreover, the army could be utilized for many productive civil tasks.

Transitional Justice

emphasizing the importance of holding accountable individuals responsible for major crimes, including severe acts of torture and organized massacres. These crimes were perpetrated by specific individuals within security branches or during notorious events such as the Hula and Baniyas massacres.. However, he also cautioned that holding everyone accountable for actions over the past 14 years could trigger a cycle of revenge and counter-revenge, destabilize the country, and lead to endless political and social upheavals:

If we pursue the right to address everything that happened over the past 14 years, it will perpetuate a cycle of revenge, counter-revenge, and internal disputes. This would lead to widespread dissatisfaction. For this reason, we have prioritized amnesty in our military approach. In military situations, one might expect brutal battles and significant bloodshed. However, we prioritized clemency and successfully entered many large areas without any bloodshed. (Al-Arabiya Interview)

This stance reflects a balance between justice and reconciliation, prioritizing accountability for major crimes while overlooking other issues to foster the building of a new future:

In major battles, revenge is generally waived, except in certain cases, such as for the officials of Seydnaya prison, the heads of the security branches, the airmen who dropped bombs and explosive barrels on civilians, and those responsible for massacres. However, justice must be pursued through the judiciary and the law, not by individuals, because we must respect the law. If we fail to do so, it will turn into the law of the jungle. (Al-Arabiya Interview)

Al-Sharaa viewed rebuilding Syria as the “greatest restitution of rights” for those affected, but he overlooked the fact that some victims may not accept this approach without clear accountability. His vision focuses on achieving rapid stability through reconciliation and amnesty, but this could face challenges if not implemented within a transparent judicial framework that ensures justice for all. Al-Sharaa did not outline a clear mechanism for implementing this proposal, such as establishing an independent transitional justice committee. This omission may raise concerns about the potential for selective justice, as it requires clear procedures and safeguards to prevent it from becoming a political settlement that favors one party at the expense of another.

He advocates for national reconciliation without a revenge-oriented mentality or political polarization, believing that a new social contract will lead to long-term stability. However, he does not explain how consensus will be achieved among the various parties regarding this contract. While he affirms that refugee returns will occur on a large scale within two years, he does not provide specific details on the policies that will facilitate their reintegration. He emphasizes that social change requires long-term strategies in education, culture, and the media, reflecting a vision of gradual reform rather than rapid, radical shifts:

The [Assad] regime has created deep divisions within society. If we allow rights to be taken in the way some propose, the state will not be built effectively. We should not approach state governance with a vengeful mentality, nor should we adopt an oppositional mindset. We have inherited the Syrian problem as it is, and we must address it with wisdom, prudence, and calm. (Al-Arabiya Interview)

Al-Sharaa’s vision prioritizes calm and national reconciliation, but it requires clear mechanisms to ensure justice, political participation, and the long-term sustainability of reconciliation.

It appears that some members of HTS and the General Security do not adhere to this vision, as there are violations that contradict the principles of transitional justice. For example, subjecting all members of the security forces, army, and police to settlements means they must prove their innocence, opening the door to holding a large number of them accountable for carrying out the orders of their superiors. Additionally, this policy includes depriving them of their salaries. The inspection campaigns conducted in specific areas, including Homs and the Syrian coast, suggest that these individuals are being targeted, which provokes negative reactions both internally and externally. This situation requires more careful handling and tighter control over such violations.

Foreign Relations and Sanctions on Syria

Al-Sharaa presented a realistic stance on Syria’s foreign policy for the coming period, emphasizing that Syria is exhausted from the war and that the current priority is reconstruction, development, and improving the standard of living, rather than pursuing hostile policies. With this statement, he aimed to reassure both the international and regional communities that the new Syria will not pose a threat to any country. This message is directed at the Western and regional powers monitoring the Syrian situation. It appears that al-Sharaa seeks to reposition Syria as a country focused on internal affairs, rather than engaging in regional conflicts, marking a significant shift from the traditional discourse of the former regime:

Syria is exhausted from war, regardless of whether it is a strong state or not. We are now in a phase where we need to focus on rebuilding, strengthening, and fostering prosperity. There should be no hostile plans directed at Syria, as it poses no danger or threat to anyone. I have stated on multiple occasions and in various settings that Syria will not be a source of threat to any country in the world. (BBC Interview)

Al-Sharaa stated that sanctions should be lifted automatically with the fall of the Assad regime. However, he overlooked the possibility that the US may not view changes in Syria as sufficient to justify an immediate end to the sanctions. He did not present a clear strategy for dealing with Washington if it refused to lift the sanctions outright, especially if Washington and its allies conditioned the lifting of sanctions on specific internal reforms, the new Syria’s foreign policies, or even on al-Sharaa’s continued leadership of the state:

We highlighted an important issue: the sanctions on Syria at this time. These sanctions were imposed due to the crimes committed by the [Assad] regime against the people, of whom we are a part. Today, the people have removed this regime. Therefore, with the regime’s removal, these sanctions should be lifted automatically. I believe that continuing them will only increase the suffering of the Syrian people. The US has presented itself as a friend to the Syrian people, and these sanctions should no longer be in place. They were imposed on the regime because it killed its own people. The people have now made their decision to remove it. We hope the new US administration will not follow the Biden administration’s approach of maintaining these sanctions and that they will be lifted without any negotiations or bargaining. (Al-Arabiya Interview)

Regarding Syria’s relationship with Russia, al-Sharaa emphasized that Russia is the second most powerful country in the world and has deep strategic ties with Syria. He noted that the Syrian army primarily relies on Russian weapons, that Syrian power stations were built with Russian expertise, and that there are strong cultural connections between the two countries. As a result, he stated that Syria will not sever its ties with Russia quickly, as some might expect. However, he also reaffirmed Syria’s independence in decision-making, asserting that any agreements made between Russia and the former regime will be reviewed based on Syria’s interests. Al-Sharaa does not seek to cut relations with Russia but aims to maintain a strategic partnership while upholding Syrian sovereignty. He does not wish to antagonize Russia but pointed out that there are “unfair” agreements that need to be reevaluated. Ultimately, he wants Syria to position itself as a “link” between international powers, rather than an arena for conflict among them.

Regarding the relationship with Iran, al-Sharaa acknowledged that Iranian expansion in Syria has been a significant problem affecting both Syria and its neighboring countries. However, he made a distinction between the Iranian people and the policies of the Iranian authorities, emphasizing that there is no hostility towards the Iranian people:

Iranian expansion in the region and turning Syria into a platform for implementing its agendas posed a significant threat to Syria, its neighbors, and the Gulf.” He added: “We were able to end the Iranian presence in Syria, but we do not harbor enmity toward the Iranian people. Our problem was with the policies that harmed our country. (Syria TV Interview)

Therefore, his vision for foreign policy can be summarized in the following points:

- Maintaining good relations with Russia while reviewing certain unfair agreements.

- Avoiding confrontation with the United States and seeking to lift sanctions through dialogue.

- Refraining from entering regional conflicts, such as the tensions between Russia and the West or between Israel and Iran.

- Strengthening relations with Turkey, Arab countries, and neighboring states, while maintaining a balance between them and avoiding involvement in any regional alliances.

Conclusion

Ahmad Al-Sharaa’s statements reflect a clear shift in his political discourse, as he aimed to present a new vision centered on reconstruction and development, rather than regional conflicts. This shift demonstrates a realistic understanding of the challenges Syria faces after years of war. It underscores the need to focus on improving the economic and living conditions of the Syrian people, while reassuring the international community that Syria will no longer pose a threat to any country. This approach seeks to ease the international isolation imposed on the country.

Al-Sharaa’s statements outline a preliminary vision for Syria’s future, marked by cautious realism. However, it lacks the executive details and clear mechanisms necessary to achieve the goals of the transitional phase. While he emphasizes institutional stability, reconstruction, and national reconciliation, the absence of a political program and a specific time frame raises significant concerns about the vision’s potential to evolve into a comprehensive and sustainable national project.

Some argue that it is unfair to expect interviews to include detailed executive programs or cover all aspects, as such demands are typically reserved for written program documents. This raises the question: Why were written visions not presented to the public? Several explanations might account for this. One possibility is that withholding a published document allows for flexibility, enabling modifications and offering a chance for ideas to evolve through verbal presentation and the feedback from the Syrian street. Another explanation suggests that the difficulty of producing a written document stems from the conflict between the Salafist visions held by the majority of HTS members and their allies, regarding Syria’s future, and the more modern, open vision favored by most Syrians. This divide centers on the nature of Syria’s system and the military force needed to maintain power.

From a comparative perspective, drawing on the experiences of countries like Iraq and Libya that have undergone political transitions after long conflicts, it is evident that success at this stage hinges on striking a delicate balance between reconciliation and justice, as well as between preserving and reforming state institutions. The process must avoid simply recycling previous elites or imposing a new political reality by force. In this context, the lack of a clear constitutional vision, the delay in launching the National Dialogue Conference, and conflicting statements about the future of political and social freedoms could undermine the potential to build a stable and sustainable state in the long term.

Additionally, external challenges, such as economic sanctions, rebuilding international relations, and the influence of regional players like Russia, Iran, and Turkey, will significantly impact the course of the transitional phase. It appears that al-Sharaa is attempting to adopt Realpolitik in addressing these issues, aiming to restore balance in international relations. However, he has yet to present a clear vision on how to manage more complex matters, such as the future of foreign presence in Syria or the mechanisms for attracting the investments needed for reconstruction in an unstable political environment.

In conclusion, the success of the next phase will depend not only on the political leadership’s will but also on the ability of Syrian society, in all its components, to establish a genuine political partnership. Additionally, it will rely on the international community’s willingness to support the country’s stability without imposing external agendas. This phase, therefore, represents a crucial test of Syria’s ability to transition from chaos and conflict to a sustainable, just, and democratic governance model that fulfills the aspirations of Syrians for freedom and dignity, while restoring Syria’s regional and international role as an independent and sovereign state.